The Bidimensional Knowledge Matrix

To read the scientific study that this article is based on, click on this link:

How Knowledge Seeking And Knowledge Chaperoning Impact Individuals And Societies

- How can good people disagree about the most fundamental aspects of how to run our communities?

- How can someone else take such clearly “wrong-headed” positions, and still be a decent person?

- I thought my coworkers were good people. Then I began to read their social media posts…

If you struggle with these questions, you are not alone. These are fundamental problems that people have wrestled with for generations. Especially in the modern era, when we are inundated with the opinions of our friends, family, and neighbors on social media.

If you struggle with these questions, you are not alone. These are fundamental problems that people have wrestled with for generations. Especially in the modern era, when we are inundated with the opinions of our friends, family, and neighbors on social media.

It used to be that we barely knew the views that those around us held. We were left to assume how they felt about politics based on very little evidence. Those we we perceived as good people, we naturally assumed agreed with us politically. Those who were grossly unpopular, rude, or who otherwise behaved inappropriately we could assume must not share our world views.

Social media has taught us otherwise. We see the post of someone we admire and realize that they don’t share our political views, but instead belong to the other party. Alternatively, we may see the post of someone who we generally have not respected, only to find out that this person thinks very similarly to ourselves.

It leaves us to wrestle with the problem highlighted above: How can good people take such wrong-headed positions!

In order to try to understand this, a researcher named Hiram Bertoch conducted a study exploring how people seek knowledge and how they chaperone their knowledge.

You can read more about each of these topics using these links:

How people seek knowledge

How people chaperone their knowledge

After struggling for years to understand what drove people towards their various political ideologies Bertoch’s work eventually led to the creation of a bidimensional knowledge matrix. This matrix explains how people seek knowledge and how they chaperone their knowledge.

How People Seek Knowledge

The first axis of the bidimensional knowledge matrix represents how individuals seek learning. According to this study 87% of individuals actively seek learning throughout their lives. These individuals care about truth, and want to know how the Universe functions. However, they do not all look to the same sources. Bertoch’s research showed that there is a divide across the knowledge seeking continuum with some looking primarily towards religious sources for truth, and others looking primarily towards scientific sources.

Those who look towards religious sources, such as scripture, a trusted spiritual advisor, prayer and so forth will often draw very different conclusions about how the Universe functions than those who look towards scientific sources.

This division isn’t surprising. Both institutions (religion and science) are actively promoting themselves in our communities as the ultimate source for truth. They don’t always agree with each other. Such as has been the case with regards to issues like abortion rights, gay marriage, and so forth. With these two powerful groups actively lobbying society it is not the least bit surprising that there would be tension between them.

It is important to note that these two institutions are not mutually exclusive. In other words, it is possible, and even common for individuals to be both highly religious and also highly scientific. Thus, our communities today are made up of a wide variety of individuals. Some of whom look exclusively to religion for truth, some who look exclusively towards science, and a lot who fall somewhere between these two extremes.

How People Chaperone Their Knowledge

Once an individual has obtained any quantity of knowledge they can then begin to use it in order to solve problems. How a person judges the value of a potential solution to a problem is referred to as knowledge chaperoning. For example, if a person facing a problem sees two potential solutions, they will select the one that they feel is best, based on how they chaperone their knowledge.

Bertoch suggests that there are two primary ways that people chaperone their knowledge. These are compassion and logic. According to his research, those who chaperone their knowledge with logic are likely to select logical solutions to problems. While those who chaperone their knowledge with compassion are likely to select more compassionate solutions to their problems.

As with knowledge seeking, it is important to note that once again, logic and compassion are not mutually exclusive. Someone can be either highly inclined towards one or the other, or they can be highly inclined towards both or neither.

Consider the effect this would have on a community trying to solve the same systemic problems. Members of that community who chaperone their knowledge with logic are going to adamantly debate the merits of solutions that seem to be most logical. While those who chaperone their knowledge with compassion are going to aggressively lobby for the solutions that seem to help the most people, or ease the most suffering. Both groups will look at each other in utter disbelief, not comprehending how the other side can support solutions that in their own views and based on the way that they chaperone their knowledge are so clearly wrong-headed.

Thus knowledge chaperoning provides a second axis for how people divide themselves in our communities.

The Bidimensional Knowledge Matrix

These two axes of division (knowledge seeking and knowledge chaperoning) can be combined together to form a matrix. Individuals can then be graphed on this matrix based on their individual tendencies towards knowledge seeking and knowledge chaperoning. It is beyond the scope of this article to explain how knowledge seeking and knowledge chaperoning are measured. Those interested in learning more about the science can read the study report here.

These two axes of division (knowledge seeking and knowledge chaperoning) can be combined together to form a matrix. Individuals can then be graphed on this matrix based on their individual tendencies towards knowledge seeking and knowledge chaperoning. It is beyond the scope of this article to explain how knowledge seeking and knowledge chaperoning are measured. Those interested in learning more about the science can read the study report here.

A person in quadrant A of this matrix would be someone who tends to seek learning from religious sources, and who tends to chaperone their knowledge with compassion. A person in quadrant B is someone who tends to seek learning from scientific sources, and who tends to chaperone their knowledge with compassion. A person in quadrant C is someone who tends to seek knowledge from religious sources and who tends to chaperone their knowledge with logic. While a person in quadrant D is someone who tends to seek learning from scientific sources, and who tends to chaperone their knowledge with logic.

Predictable Patterns Emerge

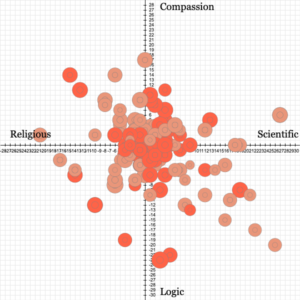

Figure 1

Charting individuals on this bidimensional knowledge matrix results in predictable and repeatable patterns emerging. Figure 1 represents a random sampling of conservatives who were charted on the matrix. Notices that these individuals largely occupy quadrants A, C, and D. With a much smaller percentage in quadrant B.

It is also important to note that there is a large percentage (41%) who are within 7 degrees of the center. Which we will discuss later in this article. Those who are outside of this central proximity of 7 are pretty evenly split amongst the three quadrants that largely make up conservatism.

Note that the darker red dots represent persons who self-reported that they are strongly conservative, while the lighter red dots represent individuals who self-reported that they are moderately conservative.

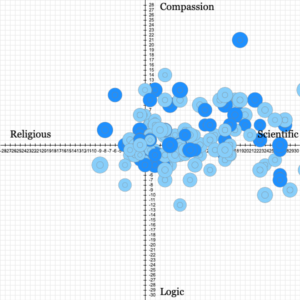

Figure 2

Figure 2 represents a random sampling of liberals who were charted across the bidimensional knowledge matrix. Unlike conservatives, these individuals largely occupy quadrant B, with very little representation in quadrants A, C, and D.

As with conservatives there are a large number of individuals (40%) who chart within 7 degrees of center. Those who chart outside of a central proximity of 7 are largely found between quadrants C and D with more in C than D.

As with conservatives, dark blue represents individuals who self-reported as strongly liberal, while light blue represents individuals who self-reported as moderately liberal.

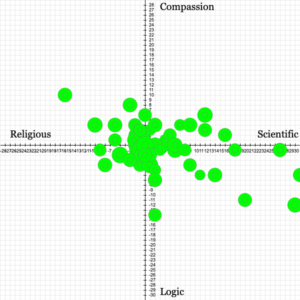

Figure 3

Figure 3 represents a random sampling of political centrists who were charged across the bidimensional knowledge matrix. You will notice that once again a very distinct pattern emerges. Once again, there is a strong tendency (46%) to fall within a central proximity of 7 degrees. Those who fall outside of this central proximity of 7 tend to fall largely in quadrant D.

These results are stunning for their consistency and predictability. While there are exceptions, where individuals who self-report as one ideology fall in the zone more common for another ideology, there is strong affiliation amongst individuals based on their political ideology.

Figure 4.

Figure 4 shows a simplified overview of how individuals tend to graph on the bidimensional knowledge matrix. Though individuals do graph outside of these zones, this is what is most common. Those self identifying as conservatives tend to graph in the red zone. Those self identifying as liberals tend to graph in the blue zone. While those who self-identify as political centrists (independents) graph in the green zone.

Central Proximity of Seven

Throughout this article we have seen that a large percentage of the population falls within a central proximity of seven. With 41% of conservatives, 40% of liberals, and 46% of centrists occupying this space. This is significant for several reasons. Firstly, there is very little difference in ideology amongst these individuals. Regardless of whether they label themselves as a conservative, a liberal, or a centrist, they tend to view the world the same. Thus, any differences can be largely attributed to tribalism.

Secondly, the research shows that individuals who fall inside a central proximity of 7 fare much better in life than individuals who fall outside a central proximity of 7. Those on the inside of this zone earn more money, have healthier relationships, have higher educations, and report greater levels of happiness than those outside of this zone.

A Note About Central Proximity

Accounting only for an individual’s central proximity on the bidimensional knowledge matrix is a bit deceiving. This is because, as has been discussed earlier, neither extreme of the two axes are mutually exclusive. A person can either score highly for both extremes or alternatively they can score low for both extremes. For example, someone who scores (50+) for scientific knowledge seeking and (50-) for religious knowledge seeking would have a net score of 0, resulting in their graphing at the center of that axis. Likewise, someone who scores (3+) for scientific knowledge seeking, and (3-) for religious knowledge seeking would also have a net score of 0. Thus, these two individuals would chart at the same place on the graph, even though they are very different.

To account for this, persons with higher raw scores are graphed with larger dots than persons with lower raw scores. More importantly, a more useful Central Proximity Ratio (CPR) score is calculated which takes into account both their position on the graph, and also the size of their tendencies on either side of the axis. It is this final score that is used to look at impact on an individual’s life and well being.

How Can This Knowledge Help You Make Sense of Your Neighbor’s Behavior?

Knowing where we individually chart on the bidimensional knowledge matrix is powerful in that it helps us understand how we see the world. Knowing that our neighbors, chart in a variety of different places on this matrix can help us understand how good people can draw such different conclusions and take such different positions from ourselves on the issues that our communities face.

It can help us realize that our initial impressions of our neighbors were not wrong. They are good people. They just seek and chaperone their knowledge differently than we do. It isn’t that they are evil, stupid, misguided, or ill-informed. It is that they are judging the correctness of solutions based on an entirely different set of criteria. In many ways it could be said that they are speaking a different language than we are.

We can choose to belittle our neighbors, and condemn them. Or alternatively we can choose to celebrate who they are and the value that their insights bring to creating pragmatic solutions that account for both logic and compassion.

The Right And The Left Need Each Other

Just as individuals who fall within a central proximity of 7 fare better in life, so to do societies that are balanced and pragmatic fare better over all. Far too often we hear it suggested that the union should be dissolved. That the red states and the blue states should separate from one another. Allowing each to then move forward inhibited by the other side.

The problem with this view is that it would create extremes, and both sides would fail as a result. The red states need the blue states, and the blue states need the red states to thrive. Too much logic, without the heart, leads to a cold and cog spinning world. Too much heart without the logic leads to bankruptcy and societal collapse.

It Isn’t The Right Vs The Left, It Is Those Who Divide Vs Those Who Unite

On the extremes of either ideology there are individuals who seek to divide society along tribal lines for their own financial or political gain. These persons teach us to hate and distrust one another based on our differences. The result being that we buy their products and vote them into office.

The reality however is that we must celebrate our differences because without them we would collapse. The fact that we need each other, makes those who are different from ourselves our counterbalance. If they fall off the pendulum, so do we. They are not the enemy. They are our most important allies!

The only enemy are those who actively work to stir up anger, contention, and mistrust. Who, instead of promoting and celebrating our differences, use these differences in order to enrich and empower themselves.

They are a very small portion of the population, but their impact is substantial. It is imperative that the rest of us point out their actions for what they are, and that we reach beyond these dividers in order to create trusting relationships across all political ideologies.

Understand that the other side is different, but they are not evil.

They view the world differently, but they are not stupid.

They seek learning from a different source, but they are not ill-informed.